Modernising our Application with TypeScript

Introduction

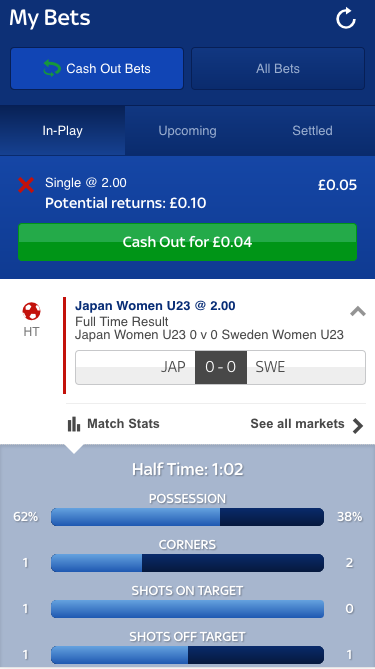

Back in October 2016 my team were looking for ways we could improve our My Bets product which was written using React. We’d first made the product about 2 and a half years ago, much before my time, when React was still fairly new on the scene. As such, the React library itself had been through quite a few changes since then and a few of our design patterns were in need of a spring clean.

As a product, My Bets allows our customers to view, track and cash out any of their bets. Bets these days are complex: they can consist of many selections with multiple outcomes across multiple events; then we need to track the history of a bet - i.e. all the data at the time it was placed compared to the equivalent, current data.

Confused? Don’t worry, you’re not alone. The important thing to note is that we needed to be able to model complex data structures and their relationships to each other. TypeScript seemed perfect for this. Like using babel, it promised to give us ES6 features ahead of time but also allowed us to add strict types to give us more control over our data structure.

What is TypeScript

If you’re not familiar with TypeScript, it’s an open source language created by Microsoft which compiles down into vanilla JavaScript. JavaScript is itself TypeScript, TypeScript is just a superset of JavaScript which includes typings and a few other bits of syntactic sugar such as Enums and Interfaces - things that you’d be used to seeing in “grown up” OOP languages.

Once you’re happy with your TypeScript, you simply run tsc (TypeScript compile). TypeScript will then perform static analysis of your code and remove all of the type hints and other TypeScript goodness and emit pure vanilla JavaScript. It will even compile from ES6 to ES5, making your code cross device friendly.

The clever part comes with the static type analysis, given all of the parameter type hints, return types, interfaces etc that you’ve written in your codebase, the compiler will analyse your code and make sure it all makes sense. This is a good thing because TypeScript is sanity checking your code for you as part of your development process, long before it ever reaches the production environment.

Other major benefits of TypeScript include:

- Better IDE support

- Support for interfaces

- Support for Enums

Refactoring our App to use TypeScript

Once we’d decided on TypeScript we needed to come up with a sensible process for upgrading our rather large, business critical application, whilst it was still being worked on by other developers.

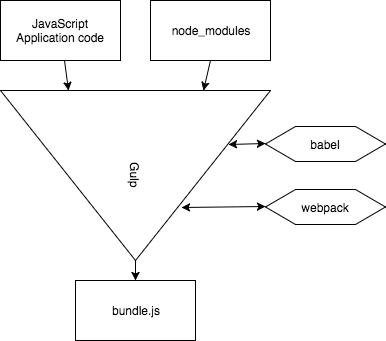

We wanted to go from a setup similar to the following:

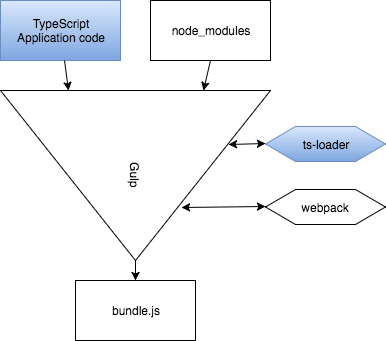

to the following:

Converting to TypeScript

Following the logic that TypeScript was just a superset of JavaScript, we were hoping it would just be a case of renaming all of our files and swapping babel for TypeScript in our build process. What actually happened was a bit different: we’d expected a couple of rough edges when we moved to TypeScript, but nothing on the scale that we experienced. Integrating TypeScript as part of the build process was rather straight forwards, but when we ran TypeScript compile on our codebase we were faced with an absolute mountain of errors at the static analysis stage.

On first pass, we were presented with about 1800 errors all looking a bit like the following:

(46,7): error TS2339: Property 'setImagePathPrepend' does not exist on type '{}'.

(50,7): error TS2339: Property 'getImagePathPrepend' does not exist on type '{}'.

(54,7): error TS2339: Property 'setBetslipOutcomeHelper' does not exist on type '{}'.

(58,7): error TS2339: Property 'addOutcomesToBetslip' does not exist on type '{}'.

(62,7): error TS2339: Property 'setShowBetAgainButton' does not exist on type '{}'.

(66,7): error TS2339: Property 'shouldShowBetAgainButton' does not exist on type '{}'.

(70,7): error TS2339: Property 'setQualifiedVideoStreams' does not exist on type '{}'.

(74,7): error TS2339: Property 'getQualifiedVideoStreams' does not exist on type '{}'.

(78,7): error TS2339: Property 'setDisableHRCashoutAfterStartTime' does not exist on type '{}'.

(82,7): error TS2339: Property 'shouldDisableHRCashoutAfterStartTime' does not exist on type '{}'.

(86,7): error TS2339: Property 'setCsrfToken' does not exist on type '{}'.

(90,7): error TS2339: Property 'getCsrfToken' does not exist on type '{}'.

(106,7): error TS2339: Property 'formatLongDate' does not exist on type '{}'.

Refactoring to ES6

We realised that we were going to have to convert from ES5 JavaScript to ES6 in order to take best advantage of the React integration with TypeScript. This worked, fundamentally, by using the Generics feature provided by TypeScript and allowed us to define what the props and state of each component looked like.

Define static methods

(74,7): error TS2339: Property 'getQualifiedVideoStreams' does not exist on type '{}'.

It turns out we were calling a lot of methods on our classes/components in a static context, without them being static. This is fine in ES5 JavaScript where there is no context of static methods or properties, but TypeScript wouldn’t be doing its job properly unless it enforced strict standards. Solving these errors was a simple case of declaring static any methods which were or could be called in a static context.

Import type definitions for external node_modules libraries that we were using

What would the modern JavaScript world be without node_modules? Well, the good news is that TypeScript supports external JavaScript modules. The bad news is that in order to fully benefit from TypeScript, each of your external modules needs its own type definitions in order to let TypeScript know how the module should behave.

With TypeScript 2.0 and above, for most of the popular modules, there should be open source TypeScript definitions for your module and it’s as simple as running:

npm install @types/<module_name> # e.g. npm install @types/react

For less popular modules, or perhaps even your own private JavaScript modules you will have to write your own definitions. Below is an example of a definition we made for the npm path module. Note - we’ve not gone to any great detail to make this complete, we’ve added just enough information to describe the methods we wanted to use in our code

Below is an example of our own type definition for the path module

declare module path {

/**

* Joins 2 url parts together

* @param part1

* @param part2

*/

function join(part1: string, part2: string);

}

export = path;

Getting the test suite up and running again

An important part of validating that our refactor hadn’t broken anything would be a successful test run. We already had reasonable unit test coverage of our components and stores using jest; the problem was jest runs using node which expects JavaScript files. The solution here was to set up a pre processor to compile our TypeScript project into JavaScript files at the start of every test run and then discard the files once the tests had been executed. I won’t go into too much detail on this part, but if this is something you’re looking to do yourself a simple search for “jest TypeScript pre-processor” should yield some easy to follow solutions.

Releasing it

We thought long and hard about how we could release our refactor in an incremental manner but due to our build process producing a single artifact, this wasn’t going to be possible without a significant re-shuffle of the way we built and released our code, so probably not worth it. We did however want as seamless a release as possible so we had to make sure everything fitted in well with our current build process. Fortunately this was made easy for us as the build process just runs gulp from our project root directory so as long as gulp could run using the same command as before and produce a single ES5 artifact in the same location as before, we would be ok.

Process wise was a little more tricky: we were about to release a change which made changes to pretty much every file in a codebase which was being worked on daily. In order to avoid a constant loop of merge conflicts we froze any other development on the codebase for 2-3 days whilst we initially brought our feature branch up to date with master (resolving many conflicts as we went!) and then had the opportunity to release and test the refactor without having to worry about new code being released behind it and complicating the whole process.

Fortunately after a full regression test of our product, the release went to plan. The only bug we encountered was a display issue with an icon tag, which probably came about as a result of bringing our branch up to date with master - this was seen as a success given the scale of the diff that we’d just released.

Result

Our My Bets product is now fully TypeScripted. We’ve not added a type hint to every parameter or method but in order to address our initial problem, we’ve added types to all of our models for bets, selections and outcomes.

Instead of looking at the codebase as a whole, we’re going to add types to parts of the code as we’re working on it. For example if I’m working on a component such as a scoreboard, displaying live football scores whilst the bet is in play, I might go into that component, think about all the props and then add in the relevant types as part of my current ticket.

We’ve found the more types we add in, the more support we get from our IDE, which is a good thing. We can click around between classes easier because the IDE can infer more from our code, this is good as it makes development easier and gives us confidence in what data structures we can expect in certain areas of our code.

Our development process is still much the same as it was before. From a development point of view, the developer can either have gulp watch running in the background or just run a build job every time they’ve done some work. The commands the developer uses with TypeScript are exactly the same as they were when we used babel.

What we’ve learnt

We’ve come a long way; what was initially a project to add a bit more clarity to our models turned into a full scale refactor of our My Bets product. The work done took a lot longer than initially planned, and there were some scary moments when we thought that the challenge of a re-factor of such a large codebase was too much: refer back to the wall of errors when we first ran TypeScript.

Key things we taken away from this project are:

- TypeScript isn’t exactly a superset of JavaScript, not all JavaScript will compile error free under TypeScript - this is a good thing though, it’s the reason we’re using TypeScript, to make our code more correct

- When you first convert to TypeScript, there are a lot of errors; sometimes this leads you to go for the solution which makes the error disappear rather than the best solution

- Upon releasing our code we noticed a few front end performance flaws, this had only become apparent upon releasing our code - which does mean that our ES6 code compiled via TypeScript was slower than our es5 code compiled via babel - but once we’d tightened up this performance flaw (under use of componentShouldUpdate), our code ran even faster than before.

- Most importantly we feel, as a team, our codebase has become easier to work with and comprehend whilst developing and besides the initial effort made to convert the codebase to TypeScript, there’s no real additional overhead when developing new features using TypeScript rather than JavaScript.