Technical Challenges We Encountered When Moving to a Serverless Architecture in AWS

In my first blog post I described the web application my squad have developed and the benefits we have seen since moving to Amazon Web Services (AWS). I then followed up with another post explaining a little more on how we made use of services provided by AWS to develop the web application using a serverless architecture. As you might imagine, refactoring our server based web application to a serverless solution required quite a shift in our thought processes. No one in the squad had designed a serverless system before so it was essential that we carried out a proof of concept to show that it would work. We have come up against various challenges both during and after the proof of concept so here I will share some of these challenges and how we have either solved them or how we are potentially looking to solve them.

Reaching Account Limits

Many services on AWS have account limits; these can be hard limits or soft limits which can be adjusted if you speak to your account manager. For IoT there is a limit called “Subscriptions per connection” which means each client can only subscribe to 50 topics. We originally created an IoT topic per fixture being traded which meant every web browser using our application would subscribe to several IoT topics. Once over 50 fixtures were being traded the browser could no longer subscribe to all available fixture topics. To resolve this we refactored how we named our topics to use a hierarchy along the lines of $part1/part2/part3/{fixtureId} which then allowed us to subscribe a browser to all available fixture topics with one subscription by using a wildcard like so $part1/part2/part3/#.

Keeping AWS Out of the PCI Footprint

As we are a company that takes card payments we must follow Payment Card Industry (PCI) standards to remain compliant. The larger our estate, the more things we must make sure adhere to these stringent standards. By deploying services into AWS and allowing them to access our on-premises services this would have brought AWS into the footprint we must cover with PCI standards; this is true even when the services in AWS do not use any card payment data. By pushing our data into our AWS services instead of pulling, then having on-premises services poll AWS to retrieve the data, we avoid exposing our on-premises systems and do not need to apply PCI standards to our AWS hosted services.

Keeping Track of Services

In my previous blog post you will notice from the architecture diagrams that we went from having a handful of components in our web application to having several times as many components. As we added more components it became increasingly difficult for everyone in the squad to know about and remember all of the components and how data flowed through the system. There are third party services that can automatically document all of your services but these require access to your account, so can be problematic for security requirements. We spent some time mapping out all of the components we had so far and used draw.io to create an architecture diagram. We are now able to export the diagram as an image and as an XML file allowing us to check them into our version control system and then import the XML file back into draw.io whenever we need to make changes.

Latencies In Our Original Design

In our proof of concept we used Kinesis data streams to decouple our components. Lambda polls Kinesis rather than Kinesis pushing to Lambda. We discovered that because of the polling delay (once per second) combined with multiple Lambdas being triggered by Kinesis it caused a large overall latency when running end to end. Upon looking into more of the AWS services we realised that SNS would be more suitable as it uses the push model. It took less than a day to swap the libraries used from Kinesis to SNS and then retest the end to end to find an average latency of milliseconds.

Potentially Unnecessary Components

During development we have reused patterns but they might not always be the best way to utilise AWS. One example is we have a pattern of using an SNS topic between two Lambdas; it could be that Step Functions will be better suited and eradicate the need for these SNS topics. We haven’t yet investigated the suitability of Step Functions but we’re open to evolving our architecture and have created a ticket to run a spike to evaluate them for our system.

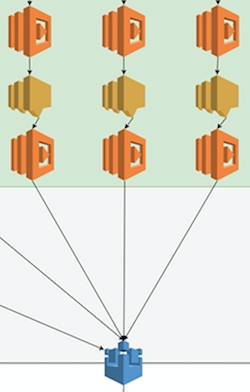

Another pattern we have used repeatedly is to deploy Lambdas between an SNS topic and IoT with the single task of passing the JSON data from the SNS onto IoT. At the moment an IoT topic cannot subscribe to SNS so we need to deploy a component to do that work for us. Whilst this is currently necessary we have raised this to our account manager as customer feedback can drive the features AWS release; maybe one day we will no longer need these bridge components to IoT.

A section of our architecture where a Lambda function has been deployed multiple times to sit between SNS and IoT, and SNS topics are used between multiple Lambdas.

A section of our architecture where a Lambda function has been deployed multiple times to sit between SNS and IoT, and SNS topics are used between multiple Lambdas.

Autoscaling Latency

When a Lambda function is invoked it may already be warm and reuse an existing container, or it may result in a cold start. When an invocation requires a cold start the jar will be downloaded from S3 and the Lambda runtime environment is created. In order to keep the latency low we want to make use of warm Lambda containers. To prevent AWS from clearing away our unused Lambda containers we send a number of requests to the Lambda function every so often so that the containers will still exist when real Lambda invocations occur and a warm invocation can take place.

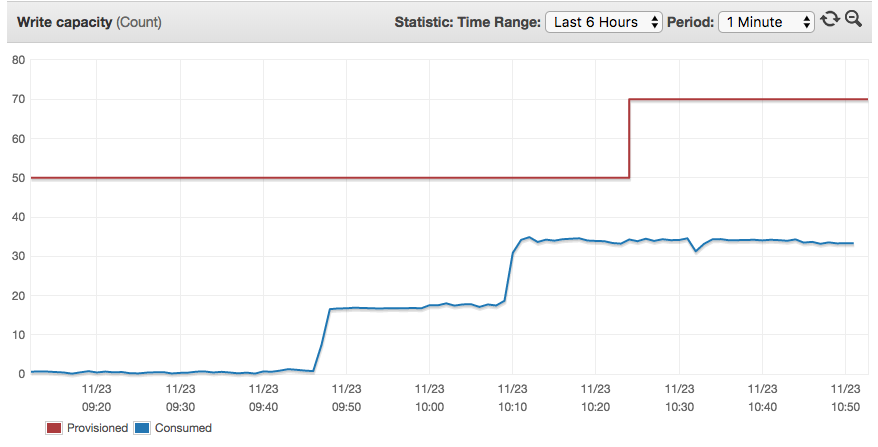

For DynamoDB there is an option to turn on autoscaling with further configuration for target utilisation and the min/max capacity. We set our target utilisation to be 50% but have discovered that it can take several minutes for the increase of provisioned capacity to take place so if the increase in usage is very rapid then we may hit the limit of provisioned capacity. This can be seen in the image below. We are looking into configuring the CloudWatch rules in our Terraform code so that the autoscaling happens sooner but until we have a better solution, we are keeping our minimum provisioned capacity higher than we require in order to account for slow movements in autoscaling. Whilst we have yet to completely iron out a fitting solution for this it is worth knowing about and being able to anticipate it.

A monitoring graph showing the latency in increasing the provisioned capacity. We passed 50% utilisation at about 10:08 but scaling did not occur until approximately 10:24.

A monitoring graph showing the latency in increasing the provisioned capacity. We passed 50% utilisation at about 10:08 but scaling did not occur until approximately 10:24.

Cloud deployments and serverless architecture are a hot topic right now but as discussed they are not without their own challenges. Some of the challenges we faced came from our lack of experience with AWS and knowledge of their offerings; other challenges came from business problems and keeping our squad working efficiently with a new style of architecture. We are constantly evaluating and evolving the various pipelines in our AWS estate, and our experience so far suggests that mistakes made in our Cloud deployments are often simple and inexpensive to fix.