How do I become a Software Engineer?

The IT industry is notoriously grandiloquent in selection of job titles. So much so that online job boards often have more than four dozen different terms for these kinds of roles, without even adding specific technologies or languages to the title.

Here at SB&G the vast majority of our hands-on technical staff have a job title of “Engineer” in some form, and irrespective of job title we’re specifically seeking engineers in our hiring process.

So just what is software engineering, and what makes it different from software development?

Today’s world is filled with easily accessible education for anyone who wants to “learn to code”, such as Codecademy, Khan Academy and even down to school coding clubs teaching Scratch. Anyone can learn to put some lines of a high level language together and produce a program that does something.

With a little effort - most people who learn to code can reach a point where they can either be employed to do so, or they can produce an app that earns them some money. Can we refer to this multitude of programming language literati as “software engineers”?

An analogy

Let us step away from the world of IT for a moment, and imagine instead the world of carpentry.

With a little imagination, and some tools, most adults could put together a few pieces of wood and some nails and call the product a stool. Depending on the effort they have gone too, it might even be sturdy, comfortable and good looking.

Again most adults can also go out to a popular warehouse store, purchase and construct a flat-pack chair. They may even make slight modifications to the resulting chair, painting it, or adding reinforcement to some areas.

There are fewer individuals who have the skills and experience necessary to construct a sturdy chair from scratch, selecting and honing the raw materials to produce a piece of fine furniture; or to design and specify the plans for a new design of flat-pack chair.

We can call those people in the third group “carpenters”, and I would be fairly irate if I were to employ a carpenter to build me a chair and be presented with either a flat-pack chair or a basically finished stool. I have certainly found myself in the first two groups from time to time, and would never consider advertising my services as a carpenter.

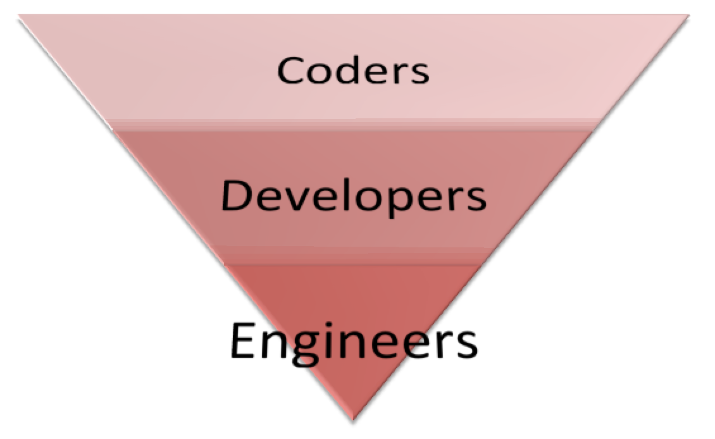

To translate these groups back into the world of IT, if we examine the group of programmers as a whole the first group are those people who have learnt how to code, but haven’t really had much experience (I’ll call this group “coders”). The second group have discovered the various frameworks that are available and can manipulate those frameworks to achieve their own ends (let’s call this group “developers”). The final group we’ll call “software engineers”, able to work from scratch and produce a well finished, refined and robust solution. Obviously this is a gross simplification and the lines between these groups are blurry and ill-defined.

IT is a black box

One of the joys IT is that most software is contained within a black box - users can only see the exterior of it and for most users that is at arms length. Either not having the interest or the knowledge to examine the HTML, CSS or client side JavaScript directly or to delve into accessible source code. For the most part the state of the interior does not matter to the end users until it breaks or starts to slow down or behave oddly under heavy usage.

In the massive marketplace that comprises IT, there is either demand or a market niche that all three types of programmer can thrive in.

There is a big market for coders to product self-published apps. Their users might find issues with what has been produced, but ultimately that comes back to the coders who can either fix it or not. They can still make money from what they have made.

Lots of potential customers in the market want to have a website, and are not technically savvy themselves. These customers are perfectly well served by developers who can pull together bits of frameworks and build an attractive front end. They can then either continue refining the features of that site, or move on knowing that for 99% of the time what they have produced will be fine. Occasionally customers are burned by this approach as their needs scale beyond the ability of the system to serve; but in general the solution will be sufficient.

At SB&G and other large organisations in which the scale, reliability and long term maintainability of a website is a primary concern and where many different people may be working on different parts in parallel; engineers are a necessity. It would be no good for us to hire a developer for a piece of work, only to find that their solution fails under the high load imposed on it and internally is difficult to debug and fix the problem.

Of course, engineers are not perfect and they can produce solutions with the same kinds of problems, but we hope that this is less likely.

How does SB&G differentiate between coders, developers and engineers?

Part of our hiring process for software engineers involves a technical test. It is not a difficult task, but the code that the candidate produces as a result helps us to determine what type of candidate they are.

To return to my analogy for a moment, we ask you to make us a chair. If we get a stool or a slightly embellished flat-pack chair, then you are unlikely to be offered a job.

So how is it that you can progress from being a developer to becoming an engineer?

Key knowledge and skills of a software engineer

An engineer has a number of key pieces of knowledge and skills in their toolbox. Many of these things are key elements of computer science degree courses, but that doesn’t meant that you need a degree to be an engineer or likewise that if you have a degree then you are an engineer.

An engineer:

- has knowledge of coding patterns and the principles behind the patterns

- designs with failure in mind

- knows about security threats and how to deal with them

- has experience of appropriate levels of abstraction

- follows best practices in their development process

So what are the best ways to gain these skills? Read. The key here is what (and who) you read.

There are thousands of online articles written by all kinds of programmers (coders, developers and engineers) - so how do you choose the things that will extend your knowledge into the realms of engineering?

Here are some names to start with that you may recognise:

- Donald Knuth

- Martin Fowler

- Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob)

- Michael Feathers

- Jeff Atwood

- Joel Spolsky

- Kent Beck

It should be no surprise that many of these authors were signatories on the agile manifesto or were instrumental in building popular large scale applications, and remain amongst the leading engineers in the world.

Here are a few suggestions of published works for your reading list:

- Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship - Robert C. Martin

- Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code - Martin Fowler (Kent Beck, John Brant, William Opdyke, and Don Roberts)

- Working Effectively with Legacy Code - Michael Feathers

- Test-Driven Development: by example - Kent Beck

- The Pragmatic Programmer - Andrew Hunt, David Thomas

Other areas to explore

Attend some conferences (or find out who is speaking, and try to watch the talks online where possible) to hear from the technical innovators about engineering problems and their solutions. These are also a good source of inspiration for bloggers and twitter accounts to follow for more titbits of knowledge.

Some things are easier to learn through practical experience. Security in particular is well represented by working groups in the open source community, mostly because the same security flaws occur again and again online. At a minimum you should be familiar with the OWASP Top 10.

Lastly, consider failure. Every problem is an opportunity to learn, even if you were not directly involved in the operational challenges at the time. What was the root cause? Was there anything that made the problem worse? Is there anything that can be done to mitigate the effects, detect it earlier, degrade more gracefully, or give the user a better experience? The bigger the failure, the more opportunities there are for learning. Seek out posts from large organisations in which they describe the resolution of problems, or what happened during a major outage - often key pieces may be mentioned that you had not previously heard of or considered as part of your own solutions.

In summary - Like a carpenter studies hard and hones their skills, study your craft, apply that knowledge to your programming and become an engineer!